Archive

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

A lot of the DM facing rules in Dungeon World seem interesting outside of the game itself. Fronts are one aspect of Dungeon World that seem to be loved by all. Presented below is the chapter from Dungeon World on Fronts. (This text was generated from the text on Github.) — RAM

Fronts are secret tomes of GM knowledge. Each is a collection of linked dangers—threats to the characters specifically and to the people, places, and things the characters care about. It also includes one or more impending dooms, the horrible things that will happen without the characters’ intervention. “Fronts” comes, of course, from “fighting on two fronts” which is just where you want the characters to be—surrounded by threats, danger and adventure.

Fronts are built outside of active play. They’re the solo fun that you get to have between games—rubbing your hands and cackling evilly to yourself as you craft the foes with which to challenge your PCs. You may tweak or adjust your fronts during play (who knows when inspiration will strike?) but the meat of them comes from preparation between sessions.

Fronts are designed to help you organize your thoughts on what opposes the players. They’re here to contain your notes, ideas, and plans for these opposing forces. When you’re in a bind your fronts are where you’re going to turn and say, “Oh, so that’s what I should do.” Consider them an organizational tool, as inspiration for present and future mayhem.

When you’re building fronts, think about all the creepy dungeon denizens, the rampaging hordes and ancient cults that you’d like to see in your game. Think in broad strokes at first and then, as you build dangers into your fronts, you’ll be able to narrow those ideas down. When you write your campaign front, think about session-to-session trends. When you write your adventure fronts, think about what’s important right here and right now. When you’re done writing a few fronts you’ll be equipped with all the tools you’ll need to challenge your players and ready to run Dungeon World.

You’ll make your campaign front and first adventure fronts after your first session. Your campaign front may not be complete when you first make it—that’s great! Just like blanks on a map, unknown parts of your campaign front are opportunities for future creativity.

After that first session you’ll also make some adventure fronts. One or two is usually a good number. If you find yourself with more adventure fronts consider leaving some possible fronts as just notes for now.

At their core, all fronts contain the same components. They sort and gather your dangers into easy-to-use clusters. There are, however, two different kinds of fronts available to you. On the session-to-session level there are your adventure fronts. These fronts will see use for a few sessions each. They’re tied to one problem and will be dealt with or cast aside as the characters wander the dungeon or uncover the plot at hand. Think of them as episodic content: “Today, on Dungeon World…”

Tying your adventure fronts together is your campaign front. While the adventure fronts will contain immediate dangers—the orcs in Hargrosh Pass, say—the campaign front contains the Dark God Grishkar who drives the orcs to their pillaging. The campaign front is the unifying element that spans all the sessions of your Dungeon World game. It will have slower-burning portents but they’ll be bigger in scope and have a deeper impact on the world. Most importantly they’ll be scarier if they’re allowed to resolve.

When a danger from an adventure front goes without resolution you’ll have to make a decision. If the danger is something you like and feel has a place in the larger world of your game don’t hesitate to move it to the campaign front. You’re able to make smaller dangers that went unresolved into bigger dangers some day later on. You can move dangers from the campaign fronts to an adventure front if they’ve come to bear, too.

Here’s how a front comes together:

Not every element of your game will warrant a danger—traps, some roving monsters, and other bits of ephemera may just be there to add context but aren’t important enough to warrant inclusion. That’s okay. Fronts are here to keep you apprised of the bigger picture. Dangers are divided into a handful of categories, each with its own name and impulse.

Every danger has a crucial motivation that drives it called its impulse. The impulse exists to help you understand that danger. What pushes it to fulfill its impending doom? Impulses can help you translate the danger into action.

When creating dangers for your front, think about how each one interacts as a facet of the front as a whole. Keep in mind the people, places, and things that might be a part of the threat to the world that the front represents. How does each danger contribute to the front?

Let’s say we have an idea for a front—an ancient portal has been discovered in the icy north. We’ll call our front “The Opening of the White Gate.”

The easiest place to start is with people and monsters. Cultists, ogre chieftains, demonic overlords, and the like are all excellent dangers. These are the creatures that have risen above mere monster status to become serious threats on their own. Groups of monsters can be dangers too—goblin tribes or a rampaging centaur khanate, for example.

For the front we’re creating, we can pick a few different groups or people who might be interested in the gate. The College of Arcanists, perhaps. There’s a golem, too, we’ve decided, that protects the forgotten portal. The golem is just an obstacle, so we won’t make him a danger.

Thinking more broadly, less obvious elements of the world can be dangers. Blasted landscapes, intelligent magical items, ancient spells woven into the fabric of time. These things fulfill the same purposes as a mad necromancer—they’re part of the front, a danger to the world.

For our front, we’ll add the gate itself as a danger.

Lastly, if we think ahead, we can include some overarching dangers. The sorts of things that are in play outside the realm of the obvious—godly patrons, hidden conspiracies and cursed prophecies waiting to be fulfilled.

Perhaps the White Gate was carved in the ancient past, hidden by a race of angels until the Day of Judgement. We’ll add the Argent Seraphim to our front as a new danger.

There’s always more dangers you could add to a front, but limit yourself to 3 at most and leave room for discovery. Like a map, blank spaces can always be filled in later. Leaving room for player contribution and future inspiration means you’ll have freedom to alter the front and make it fit the game. Not every bad thing that could happen deserves to be made into a danger. If you’re uncertain, think about it this way: dangers can always get worse.

A barbarian tribe near the gate, the frozen tundra itself, a band of rival adventurers; all these things could be dangerous elements of the game but they’re not important enough just yet to deserve to be dangers.

Creating dangers is a way to slice up your overall front concept into smaller, easier to manage pieces. Dangers are tools for adding detail to the right parts of the front and for making the front easier to manage in the long run.

Once you’ve named and added a danger to the front you need to choose a type for that danger from the list below. Alternately, you can use the list of types to inspire dangers: with your front in mind, peruse the list and pick one or two that fit.

For our three dangers (The College of Arcanists, The White Gate and the Argent Seraphim) we’ve selected Cabal, Dark Portal and Choir of Angels, respectively.

Write up something short to remind you just what this danger is about, something to describe it in a nutshell. Don’t worry about where it’s going or what could happen—grim portents and the impending doom will handle that for you; you’ll get to those in a bit. If there are multiple people involved in the danger (an orc warlord and his clansmen, a hateful god and his servants) go ahead and give them names and a detail or two now. Leave yourself some space as you’ll be adding to this section as you play.

Sometimes a danger will suggest a move that isn’t covered by any existing ones. You can write custom moves to fill the gaps or to add the right effects for the danger. They can be player moves or GM moves, as you see fit. Of course, if you’re writing a player move, keep your hands off the dice and mind the basic structure of a move. A 10+ is a complete success, while a 7–9 is a partial success. On a miss, maybe the custom move does something specific, or maybe not—maybe you just get to make a move or work towards fulfilling a grim portent. The formatting of these moves varies from move to move.

For the Opening of the White Gate, I just know some fool PC is going to end up in the light that spills from the gate, so I’m writing a move to show what might occur.

When you stand in the presence of the Light From Beyond, roll+WIS:

✴ On a 10+ you are judged worthy, the Argent Seraphim will grant you a vision or boon. ✴ On a 7-9 you are under suspicion and see a vision of what dark fate might befall you if you do not correct your ways. ✴ On a miss, thou art weighed in the balance and art found wanting.

Grim portents are dark designs for what could happen if a danger goes unchecked. Think about what would happen if the danger existed in the world but the PCs didn’t—if all these awful things you’ve conjured up had their run of the world. Scary, huh? The grim portents are your way to codify the plans and machinations of your dangers. A grim portent can be a single interesting event or a chain of steps. When you’re not sure what to do next, push your danger towards resolving a grim portent.

More often than not grim portents have a logical order. The orcs tear down the city only after the peace talks fail, for example. A simple front will progress from bad to worse to much worse in a clear path forward. Sometimes, grim portents are unconnected pathways to the impending doom. The early manifestations of danger might not all be related. It’s up to you to decide how complex your front will be. Whenever a danger comes to pass, check the other dangers in the front. In a complex front, you may need to cross off or alter the grim portents. That’s fine, you’re allowed. Keep scale in mind, too. Grim portents don’t all have to be world-shaking. They can simply represent a change in direction for a danger. Some new way for it to cause trouble in the world.

Think of your grim portents as possible moves waiting in the wings. When the time is right, unleash them on the world.

I’ve chosen a few grim portents for my new front.

When a grim portent comes to pass, check it off—the prophecy has come true! A grim portent that has come to pass might have ramifications for your other fronts, too. Have a quick look when your players aren’t demanding your attention and feel free to make changes. One small grim portent may resound across the whole campaign in subtle ways.

You can advance a grim portent descriptively or prescriptively. Descriptively means that you’ve seen the change happen during play, so you mark it off. Maybe the players sided with the goblin tribes against their lizardman enemies—now the goblins control the tunnels. Lo and behold, this was the next step in a grim portent. Prescriptive is when, due to a failed player move or a golden opportunity, you advance the grim portent as your hard move. That step comes to pass, show its effects and keep on asking, “What do you do, now?”

At the end of every danger’s path is an impending doom. This is the final toll of the bell that signals the danger’s triumphant resolution. When a grim portent comes to pass the impending doom grows stronger, more apparent and present in the world. These are the very bad things that every danger, in some way, seeks to bring into effect. Choose one of the types of impending dooms and give it a concrete form in your front. These often change in play, as the characters meddle in the affairs of the world. Don’t fret, you can change them later.

When all of the grim portents of a danger come to pass, the impending doom sets in. The danger is then resolved but the setting has changed in some meaningful way. This will almost certainly change the front at large as well. Making sure that these effects reverberate throughout the world is a big part of making them feel real.

Your stakes questions are 1-3 questions about people, places, or groups that you’re interested in. People include PCs and NPCs, your choice. Remember that your agenda includes “Play to find out what happens?” Stakes are a way of reminding yourself what you want to find out.

Stakes are concrete and clear. Don’t write stakes about vague feelings or incremental changes. Stakes are about important changes that affect the PCs and the world. A good stakes question is one that, when it’s resolved, means that things will never be the same again.

The most important thing about stakes is that you find them interesting. Your stakes should be things that you genuinely want to know, but that you’re also willing to leave to be resolved through play. Once you’ve written it as a stake, it’s out of your hands, you don’t get to just make it up anymore. Now you have to play to find out.

Playing to find out is one of the biggest rewards of playing Dungeon World. You’ve written down something tied to events happening in the world that you want to find out about—now you get to do just that.

Once you have your stakes your front is ready to play.

My stakes questions include, as tailored to my group:

Often a front will be resolved in a simple and straightforward manner. A front representing a single dungeon may have its dangers killed, turned to good, or overcome by some act of heroism. In this case the front is dissolved and set aside. Maybe there are elements of the front—dangers that go unresolved or leftover members of a danger that’s been cleared—that live on. Maybe they move to the campaign front as brand new dangers?

The campaign front will need a bit more effort to resolve. It’ll be working slowly and subtly as the course of the campaign rolls along. You won’t introduce or resolve it all at once, but in pieces. The characters work towards defeating the various minions of the big bad that lives in your campaign front. In the end, though, you’ll know that the campaign front is resolved when the Dark God is confronted or the undead plague claims the world and the heroes emerge bloodied but victorious or defeated and despairing. Campaign fronts take longer to deal with but in the end they’re the most satisfying to resolve.

When a front is resolved take some extra time to sit down and look at the aftermath. Did any grim portents come to pass? Even if a danger is stopped, if any grim portents are fulfilled, the world is changed, if only in subtle ways. Keep this in mind when you write your future fronts. Is there anyone who could be moved from the now-defeated front to somewhere else? Anyone get promoted or reduced in stature? The resolution of a front is an important event!

When you resolve an adventure front usually that means the adventure itself has been resolved. This is a great time to take a break and look at your campaign front. Let it inspire your next adventure front. Write up a new adventure front or polish off one you’ve been working on, draw a few maps to go with it and get ready for the next big thing.

As you start your campaign you’re likely to have a lightly detailed campaign front and one or two detailed adventure fronts. Characters may choose, part-way through an adventure, to pursue some other course. You might end up with a handful of partly-resolved adventure fronts. Not only is this okay, it’s a great way to explore a world that feels alive and organic. Always remember, fronts continue along apace no matter whether the characters are there to see them or not. Think offscreen, especially where fronts are concerned.

When running two adventure fronts at the same time they can be intertwined or independent. The anarchists corrupting the city from the inside are a different front from the orcs massing outside the walls, but they’d both be in play at once. On the other hand one dungeon could have multiple fronts at play within its walls: the powers and effects of the cursed place itself and the warring humanoid tribes that inhabit it.

A situation warrants multiple adventure fronts when there are multiple impending dooms, all equally potent but not necessarily related. The impending doom of the anarchists is chaos in the city, the impending doom of the orcs is its utter ruination. They are two separate fronts with their own dangers. They’ll deal with each other, as well, so there’s some room for the players choosing sides or attempting to turn the dangers of one front against the other.

When dealing with multiple adventure fronts the players are likely to prioritize. The cult needs attention now, the orcs can wait, or vice versa. These decisions lead to the slow advancement of the neglected front, eventually causing more problems for the characters and leading to new adventures. This can get complex once you’ve got three or four fronts in play. Take care not to get overwhelmed.

Impulse: to absorb those in power, to grow

Grim Portents:

Impending Doom: Usurpation

Impulse: to disgorge demons

Grim Portents:

Impending Doom: Destruction

Impulse: to pass judgement

Grim Portents:

Impending Doom: Tyranny

An ancient gate, buried for aeons in the icy north. It opens into a realm of pure light, guarded by the Argent Seraphim. It was crafted only to be opened at Judgement Day, so that the Seraphim could come forth and purge the realm of men. It was recently uncovered by the College of Arcanists, who do not yet understand its terrible power.

When you stand in the presence of the Light From Beyond, roll+WIS.

✴ On a 10+ you are judged worthy, the Argent Seraphim will grant you a

vision or boon.

✴ On a 7-9 you are under suspicion and see a vision of what dark fate

might befall you if you do not correct your ways.

✴ On a miss, thou art weighed in the balance and art found wanting.

Much of the adventuring life is spent in dusty, forgotten tombs or in places of terror and life-threatening danger. It’s commonplace to awaken from a short and fitful rest still deep in the belly of the world and surrounded by foes. When the time comes to emerge from these places—whether laden with the spoils of battle or beaten and bloody—an adventurer seeks out safety and solace.

These are the comforts of civilization: a warm bath, a meal of mead and bread, the company of fellow men and elves and dwarves and halflings. Often thoughts of returning to these places are all that keep an adventurer from giving up altogether. All fight for gold and glory but who doesn’t ache for a place to spend that gold and laugh around a fire, listening to tales of folly and adventure?

This chapter covers the wider world—the grand and sweeping scope outside the dungeon. The always marching movement of the GM’s fronts will shape the world and, in turn, the world reflects the actions the players take to stop or redirect them.

We call all the assorted communities, holds, and so on where there’s a place to stay and some modicum of civilization steadings, as in “homestead.” Steadings are places with at least a handful of inhabitants, usually humans, and some stable structures. They can be as big as a capital city or as small as few ramshackle buildings.

Remember how you started the first session? With action either underway or impending? At some point the characters are going to need to retreat from that action, either to heal their wounds or to celebrate and resupply.

When the players leave the site of their first adventure for the safety of civilization it’s time to start drawing the campaign map. Take a large sheet of paper (plain white if you like or hex-gridded if you want to get fancy), place it where everyone can see, and make a mark for the site of the adventure. Use pencil: this map will change. It can be to-scale and detailed or broad and abstract, depending on your preference, just make it obvious. Keep the mark small and somewhere around the center of the paper so you have space to grow.

Now add the nearest steading, a place the characters can go to rest and gather supplies. Draw a mark for that place on the map and fill in the space between with some terrain features. Try to keep it within a day or two of the site of their first adventure—a short trip through a rocky pass or some heavy woods is suitable, or a wider distance by road or across open ground.

When you have time (after the first session or during a snack break, for example) use the rules to create the first steading. Consider adding marks for other places that have been mentioned so far, either details from character creation or the steading rules themselves.

##While You’re In Town…

When the players visit a steading there are some special moves they’ll be able to make. These still follow the fictional flow of the game. When the players arrive, ask them “What do you do?” The players’ actions will, more often than not, trigger a move from this list. They cover respite, reinvigoration, and resupply—opportunities for the players to gather their wits and spend their treasure. Remember that a steading isn’t a break from reality. You’re still making hard moves when necessary and thinking about how the players’ actions (or inaction) advances your fronts. The impending doom is always there, whether the players are fighting it in the dungeon or ignoring it while getting drunk in the local tavern.

Don’t let a visit to a steading become a permanent respite. Remember, Dungeon World is a scary, dangerous place. If the players choose to ignore that, they’re giving you a golden opportunity to make a hard move. Fill the characters’ lives with adventure whether they’re out seeking it or not. These moves exist so you can make a visit to town an interesting event without spending a whole session haggling over the cost of a new baldric.

A steading is any bit of civilization that offers some amount of safety to its inhabitants. Villages, towns, keeps, and cities are the most common steadings. Steadings are described by their tags. All steadings have tags indicating prosperity, population, and defenses. Many will have tags to illustrate their more unusual properties.

Steadings are differentiated based on size. The size indicates roughly how many people the steading can support. The population tag tells you if the current population is more than or less than this amount.

Villages are the smallest steadings. They’re usually out of the way, off the main roads. If they’re lucky they can muster some defense but it’s often just rabble with pitchforks and torches. A village stands near some easily exploitable resource: rich soil, plentiful fish, an old forest, or a mine. There might be a store of some sort but more likely its people trade among themselves. Coin is scarce.

Towns have a hundred or so inhabitants. They’re the kind of place that springs up around a mill, trading post, or inn and usually have fields, farms, and livestock of some kind. They might have a standing militia of farmers strong enough to wield a blade or shoot a bow. Towns have the basics for sale but certainly no special goods. Usually they’ll focus on a local product or two and do some trade with travelers.

A keep is a steading built specifically for defense—sometimes of a particularly important location like a river delta or a rich gold mine. Keeps are found at the frontier edges of civilization. Inhabitants are inured to the day-to-day dangers of the road. They’re tough folks that number between a hundred and a thousand, depending on the size of the keep and the place it defends. Keeps won’t often have much beyond their own supplies, traded to them from nearby villages, but will almost always have arms and armor and sometimes a rare magical item found in the local wilds.

From bustling trade center to sprawling metropolis, the city represents the largest sort of steading in Dungeon World. These are places where folk of many races and kinds can be found. They often exist at the confluence of a handful of trade routes or are built in a place of spiritual significance. They don’t often generate their own raw materials for trade, relying on supplies from villages nearby for food and resources, but will always have crafted goods and some stranger things for sale to those willing to seek them.

Prosperity indicates what kinds of items are usually available. Population indicates the number of inhabitants relative to the current size of the steading. Defenses indicate the general scope of arms the steading has. Tags in these categories can be adjusted. -Category means to change the steading to the next lower tag for that category (so Moderate would become Poor with -Prosperity). +Category means to change the steading to the next higher tag (so Shrinking becomes Steady with +Population). Tags in those categories can also be compared like numbers. Treat the lowest tag in that category as 1 and each successive tag as the next number (so Dirt is 1, Poor is 2, etc.).

Tags will change over the course of play. Creating a steading provides a snapshot of what that place looks like right now. As the players spend time in it and your fronts progress the world will change and your steadings with it.

You add your first steading when you create the campaign map—it’s the place the players go to rest and recover. When you first draw it on the map all you need is a name and a location.

When you have the time you’ll use the rules below to create the steading. The first steading is usually a village, but you can use a town if the first adventure was closely tied to humans (for example, if the players fought a human cult). Create it using the rules below.

Once you’ve created the first steading you can add other places referenced in its tags (the oath, trade, and enmity tags in particular) or anywhere else that’s been referred to in play. Don’t add too much in the first session, leave blanks and places to explore.

As play progresses the characters will discover new locales and places of interest either directly, by stumbling upon them in the wild, or indirectly, by hearing about them in rumors or tales. Add new steadings, dungeons, and other locations to the map as they’re discovered or heard about. Villages are often near a useful resource. Towns are often found at the point where several villages meet to trade. Keeps watch over important locations. Cities rely on the trade and support of smaller steads. Dungeons can be found anywhere and in many forms.

Whenever you add a new steading use the rules to decide its tags. Consider adding a distinctive feature somewhere nearby. Maybe a forest, some old standing stones, an abandoned castle, or whatever else catches your fancy or makes sense. A map of only steadings and ruins with nothing in between is dull; don’t neglect the other features of the world.

Dirt: Nothing for sale, nobody has more than they need (and they’re lucky if they have that). Unskilled labor is cheap.

Poor: Only the bare necessities for sale. Weapons are scarce unless the steading is heavily defended or militant. Unskilled labor is readily available.

Moderate: Most mundane items are available. Some types of skilled laborers.

Wealthy: Any mundane item can be found for sale. Most kinds of skilled laborers are available, but demand is high for their time.

Rich: Mundane items and more, if you know where to find them. Specialist labor available, but at high prices.

Exodus: The steading has lost its population and is on the verge of collapse.

Shrinking: The population is less than it once was. Buildings stand empty.

Steady: The population is in line with the current size of the steading. Some slow growth.

Growing: More people than there are buildings.

Booming: Resources are stretched thin trying to keep up with the number of people.

None: Clubs, torches, farming tools.

Militia: There are able-bodied men and women with worn weapons ready to be called, but no standing force.

Watch: There are a few watchers posted who look out for trouble and settle small problems, but their main role is to summon the militia.

Guard: There are armed defenders at all times with a total pool of less than 100 (or equivalent). There is always at least one armed patrol about the steading.

Garrison: There are armed defenders at all times with a total pool of 100–300 (or equivalent). There are multiple armed patrols at all times.

Battalion: As many as 1,000 armed defenders (or equivalent). The steading has manned maintained defenses as well.

Legion: The steading is defended by thousands of armed soldiers (or equivalent). The steading’s defenses are intimidating.

Safe: Outside trouble doesn’t come here until the players bring it. Idyllic and often hidden, if the steading would lose or degrade another beneficial tag get rid of safe instead.

Religion: The listed deity is revered here.

Exotic: There are goods and services available here that aren’t available anywhere else nearby. List them.

Resource: The steading has easy access to the listed resource (e.g., a spice, a type of ore, fish, grapes). That resource is significantly cheaper.

Need: The steading has an acute or ongoing need for the listed resource. That resource sells for considerably more.

Oath: The steading has sworn oaths to the listed steadings. These oaths are generally of fealty or support, but may be more specific.

Trade: The steading regularly trades with the listed steadings.

Market: Everyone comes here to trade. On any given day the available items may be far beyond their prosperity. +1 to supply.

Enmity: The steading holds a grudge against the listed steadings.

History: Something important once happened here, choose one and detail or make up your own: battle, miracle, myth, romance, tragedy.

Arcane: Someone in town can cast arcane spells for a price. This tends to draw more arcane casters, +1 to recruit when you put out word you’re looking for an adept.

Divine: There is a major religious presence, maybe a cathedral or monastery. They can heal and maybe even raise the dead for a donation or resolution of a quest. Take +1 to recruit priests here.

Guild: The listed type of guild has a major presence (and usually a fair amount of influence). If the guild is closely associated with a type of hireling, +1 to recruit that type of hireling.

Personage: There’s a notable person who makes their home here. Give them a name and a short note on why they’re notable.

Dwarven: The steading is significantly or entirely dwarves. Dwarven goods are more common and less expensive than they typically are.

Elven: The steading is significantly or entirely elves. Elven goods are more common and less expensive than they typically are.

Craft: The steading is known for excellence in the listed craft. Items of their chosen craft are more readily available here or of higher quality than found elsewhere.

Lawless: Crime is rampant; authority is weak.

Blight: The steading has a recurring problem, usually a type of monster.

Power: The steading holds sway of some type. Typically political, divine, or arcane.

Graybark, Nook’s Crossing, Tanner’s Ford, Goldenfield, Barrowbridge, Rum River, Brindenburg, Shambles, Covaner, Enfield, Crystal Falls, Castle Daunting, Nulty’s Harbor, Castonshire, Cornwood, Irongate, Mayhill, Pigton, Crosses, Battlemoore, Torsea, Curland, Snowcalm, Seawall, Varlosh, Terminum, Avonia, Bucksburg, Settledown, Goblinjaw, Hammerford, Pit, The Gray Fast, Ennet Bend, Harrison’s Hold, Fortress Andwynne, Blackstone

By default a village is Poor, Steady, Militia, Resource (your choice) and has an Oath to another steading of your choice. If the village is part of a kingdom or empire choose one:

Choose one problem:

By default a town is Moderate, Steady, Watch, and Trade (two of your choice). If the town is listed as Trade by another steading choose one:

Choose one problem:

By default a keep is Poor, Shrinking, Guard, Need (Supplies), Trade (someplace with supplies), Oath (your choice). If the keep is owed fealty by at least one settlement choose one:

Choose one problem

By default a city is Moderate, Steady, Guard, Market, and Guild (one of your choice). It also has Oaths with at least two other steadings, usually a town and a keep. If the city has trade with at least one steading and fealty from at least one steading choose one:

Choose one problem:

Your steadings are not the only thing on the campaign map. In addition to steadings and the areas around them your fronts will appear on the map, albeit indirectly.

Fronts are organizational tools, not something the characters think of, so don’t put them on the map directly. The orcs of Olg’gothal may be a front but don’t just draw them on the map. Instead for each front add some feature to the map that indicates the front’s presence. You can label it if you like, but use the name that the characters would use, not the name you gave the front.

For example, the orcs of Olg’gothal could be marked on the map with a burning village they left behind, fires in the distance at night, or a stream of refugees. Lord Xothal, a lich, might be marked by the tower where dead plants take root and grow.

As your fronts change, change the map. If the players cleanse Xothal’s tower redraw it. If the orcs are driven off erase the crowds of refugees.

The campaign map is updated between sessions or whenever the players spend significant downtime in a safe place. Updates are both prescriptive and descriptive: if an event transpires that, say, gathers a larger fighting force to a village, update the tags to reflect that. Likewise if a change in tags mean that a village has a bigger fighting force you’ll likely see more armored men in the street.

Between each session check each of the conditions below. Go down the list and check each condition for all steadings before moving to the next. If a condition applies, apply its effects.

When a village or town is booming and its prosperity is above moderate you may reduce prosperity and defenses to move to the next largest type. New towns immediately gain market and new cities immediately gain guild (your choice).

When a steading’s population is in exodus and its prosperity is poor or less it shrinks. A city becomes a town with a steady population and +prosperity. A keep becomes a town with +defenses and a steady population. A town becomes a village with steady population and +prosperity. A village becomes a ghost town.

When a steading has a need that is not fulfilled (through trade, capture, or otherwise) that steading is in want. It gets either -prosperity, -population, or loses a tag based on that resource like craft or trade, your choice.

When trade is blocked because the source of that trade is gone, the route is endangered, or political reasons, the steading has a choice: gain need (a traded good) or take -prosperity.

When control of a resource changes remove that resource from the tags of the previous owner and add it to the tags of the new owner (if applicable). If the previous owner has a craft or trade based on that resource they now have need (that resource). If the new owner had a need for that resource, remove it.

When a steading has more trade than its current prosperity it gets +prosperity.

When a steading has a resource that another steading needs unless enmity or other diplomatic reasons prevent it they set up trade. The steading with the resource gets +prosperity and their choice of oaths, +population, or +defenses; the steading with the need erases that need and adds trade.

When a steading has oaths to a steading under attack that steading may take -defenses to give the steading under attack +defenses.

When a steading is surrounded by enemy forces it suffers losses. If it fights back with force it gets -defenses. If its new defenses are watch or less it also gets -prosperity. If it instead tries to wait out the attack it gets -population. If its new population is shrinking or less it loses a tag of your choice. If the steading’s defenses outclass the attacker’s (your call if it’s not clear, or make it part of an adventure front) the steading is no longer surrounded.

When a steading has enmity against a weaker steading they may attack. Subtract the distance (in rations) between the steadings from the steading with enmity’s defenses. If the result is greater than the other steading’s defenses +defense for each step of size difference (village to town, town to keep, keep to city) they definitely attack. Otherwise it’s your call: has anything happened recently to stoke their anger? The forces of the attacker embattle the defender, while they maintain the attack they’re -defenses.

When two steadings both attack each other their forces meet somewhere between them and fight. If they’re evenly matched they both get -defenses and their troops return home. If one has the advantage they take -defenses while the other takes -2 defenses.

The conditions above detail the most basic of interactions between steadings, of course the presence of your fronts and the players mean things can get far more complex. Since tags are descriptive, add them as needed to reflect the players’ actions and your fronts’ effects on the world.

*Like Dungeon World, this page is is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. *

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

I’ve been helping Chris play test his new Skirmish game GRIMLITE since he started writing it back in May. (I use the terms “helping” and “play test” loosely.) To give the exercise some more meaning I’ve tried to link my games up into a narrative campaign. I am playing a Warcry campaign with Evan at the moment, and so i’ve set these solo games on the same planet our games are taking place. I am hoping laying all of this out and sharing how I approach playing will be useful to someone else who wants to get into solo narrative war gaming.

I’m using an initiative system similar to Bolt Action or Troika, instead of the alternating activations rules of GRIMLITE. Each unit in your warband is assigned a card, as are each type of Horror. You draw a card from the deck and that unit acts. When all the cards are drawn the round ends. This simulates a fog of war, but also makes playing a game where you control all the units a bit more interesting and fun.

I am playing solely with Horrors at the moment, rather than a rival warband I also control. My suggestion if you go this route is to use 6 points of horrors, where a lesser horror is 1 point, and a greater horror is 2. The horrors in their current state vary a fair bit in power, so you will likely need to play around with things to see how your units fare. When you are playing alone I think it’s likely more fun or interesting to ratchet up the difficulty of the game, so winning is a real challenge.

Campaigns:

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

In 1975 Gary Gygax wrote an article describing a simple approach to creating a campaign world over 5 weeks, which you could then expand upon through play: like God intended. Ray Otus took this article and expanded on its ideas to create a structured work book with concrete steps for each week and his own example of creating a small campaign setting. Recently Dungeon Possum posted about his plans to go through this process. This got me interested in doing the same. I am keen to create a basic-ass fantasy setting. I normally gravitate towards Gonzo He-Man nonsense. Playing Dark Souls and Demon Souls over the last year has me interested in Arthurian fantasy—by way of a confused Japanese man. And so that’s what I will go with. We’ll call it Misericorde for now, until I figure out the names for things in this setting. — Ramanan, Feb 2022

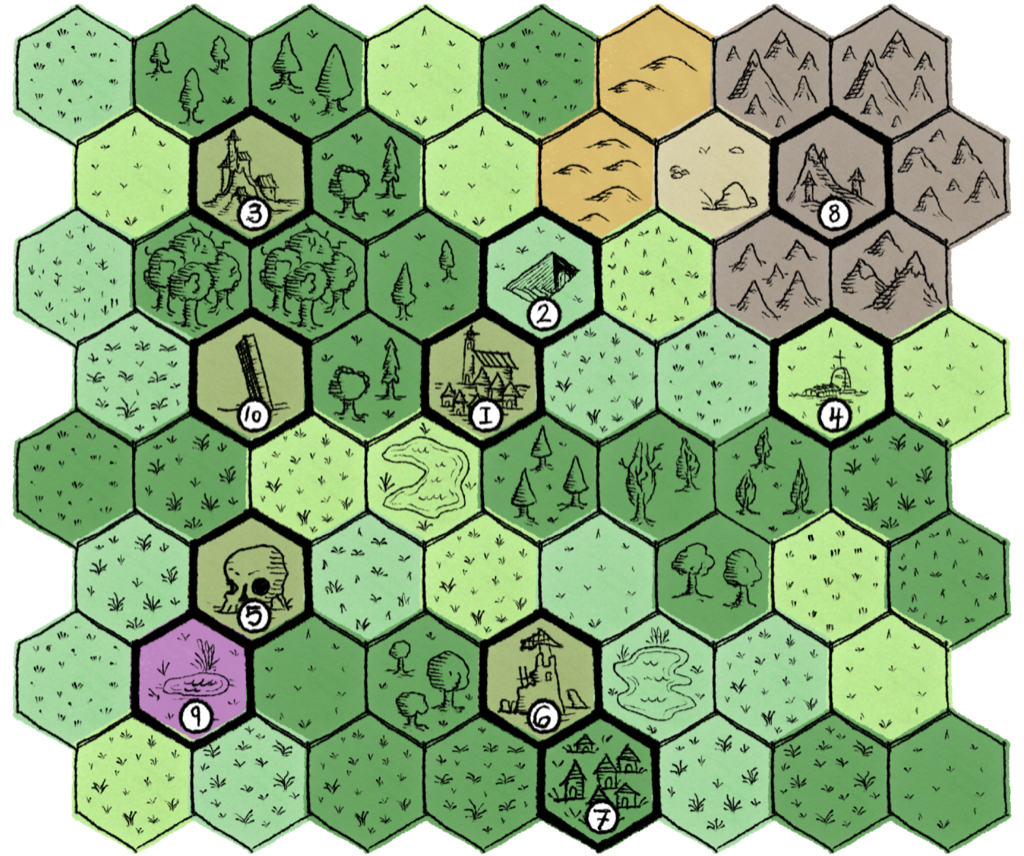

Play begins in the town of Llangolen. The Hidden Crypt is known to the players’ characters and the townspeople. It is a burial site from ages past, accidentally unearthed, no doubt full of treasure, mystery, and danger. Some other points of interest are noted below, and labeled on the map above. (The map was created using Hex Kit, with tiles by Thomas Novosel.)

An example random encounter table for the area near the Town of Llangolen. The random encounter tables would change depending on the hex the players find themselves in.

| 2d6 | Encounter |

|---|---|

| 2 | A Knight of the Good King |

| 3 | Man-eater the Troll |

| 4 | Wizard and Hangers On |

| 5 | Undead (Skeletons, Ghouls, Wraiths) |

| 6 | Bandits |

| 7 | Travellers |

| 9 | Local Militia |

| 10 | Questing Knight and Retinue |

| 11 | Gogol the Giant |

| 12 | The Dragon |

The Twenty Knights of the Good King

| d20 | Knights of the Good King |

|---|---|

| 1. | Agralan the Gloom Knight |

| 2. | Sina the Star Knight |

| 3. | The Blood Knight |

| 4. | The Chalice Knight |

| 5. | The Lion Knight |

| 6. | The Beetle Knight |

| 7. | The Lotus Knight |

| 8. | The Storm Knight |

| 9. | The Gold Knight |

| 10. | The Twilight Knight |

| 11. | The Swan Knight |

| 12. | The Bastard Knight |

| 13. | The Songbird Knight |

| 14. | The Silk Knight |

| 15. | The Emerald Knight |

| 16. | The Pumpkin Knight |

| 17. | The Crucible Knight |

| 18. | The Robber Knight |

| 19. | The Salt Knight |

| 20. | The Forgotten Knight |

Coming soon? …

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

Brendan would call this a method of play. The rules that follow are based heavily on his Hazard system, and add some structure to the loose rules presented in the OD&D booklets.

The Hazard die is a d6 that makes this all go.

The start of each session—or the time between sessions—will usually begin in a settlement. While in a settlement players may run through the following activities, in sequence.

A haven turn is assumed to be one week of in game time, though this time may vary if a shorter or longer duration would make more sense.

Upkeep costs include paying for accommodations, food and pay owed to retainers and henchmen.

There are 4 wilderness actions: move, camp, hunt & forage for food, and explore. Characters may take two actions during the day, and one at night.

The DM’s map of Carcosa is divided up into 10 mile hexes. There are no short simple trips through the wilderness. The world of Carcosa lacks proper roads, with much of the planet a rocky badland. Moving allows players to travel from hex to the next. (Some hexes, like those covered in mountains or filled with swamps, may require characters use more than one move action to get through.)

Characters generally rest at night by Camping. Skipping a camp action puts the characters at a -2 for all rolls during the following day.

Hunting and Foraging for Food can be done to attempt to find food (rations) in the wild.

Exploring will reveal a random unknown location within the hex. The players may instead attempt to find a specific location they know is somewhere in the hex. If the location is well hidden, doing so requires the character with the highest wisdom score roll under their wisdom.

After each action roll the Hazard die and resolve any hazards:

If Lost the player characters end up in a random hex adjacent to where they started. If players are traveling to a location they are familiar with this roll might not make sense. In that case, roll a d6 again. If it comes up 4 again the party is indeed lost. They somehow messed up a simple trip.

Traveling at night is more dangerous: a roll of 5 on the hazard dice is also an encounter.

Each region will have its own encounter and wilderness complication tables.

At the start of each day roll for weather and the colour of the sky. For most of Carcosa we will use the following table:

| 2-12 | Weather |

|---|---|

| 2-3 | Hot |

| 4-6 | Clear |

| 6-7 | Clearing |

| 8-9 | Overcast |

| 10 | Light Rain |

| 11 | Rain |

| 12 | Hard Rain |

Some travel complications may also effect the weather.

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

Assume we are playing an Original D&D game with the following exceptions outlined below.

Whenever you are asked to roll a dCarcosa roll all the dice: a d4, d6, d8, d10, d12 and d20! The d20 tells you which of the dice rolled should be read:

| d20 | Dice to Use |

|---|---|

| 1-4 | d4 |

| 5-8 | d6 |

| 9-12 | d8 |

| 13-16 | d10 |

| 17-20 | d12 |

You will use a dCarcosa to roll your hit dice and damage.

In traditional OD&D a hit dice is a d6. In this game a hit dice is a dCarcosa.

HP is recovered as one of the steps during the “Haven Turn” (see below). There is no (natural) partial HP recovery during a session. (Your characters don’t feel rested if you haven’t rested.)

Roll 3d6 in order for your stats. They provide no bonuses for high scores, or detriments for low scores. They are sometimes used to determine the success of actions your character wishes to perform, and to give you a rough sense of what your character might be like.

Players can pick from the following classes: Fighter or Sorcerer as described in Carcosa.

The most common adventurer is the fighter, skilled in the use of all armour and weaponry. They have a +1 bonus to their to-hit rolls at first level (as noted in their to-hit table below).

The Sorcerer is similar to a fighter, but can also learn to cast the horrific sorcery of the ancient Snake-Men. A sorcerer can learn any number of rituals, and cast them as often as they like, though the costs to do so are quite high to say the least. Sorcerous rituals banish, conjure, invoke, bind, torment, or imprison entities such as the Old Ones and their spawn. All rituals (except for rituals of banishment) require human sacrifice, and all except banishing require long ceremonies (typically at least an hour) to perform along with much paraphernalia. (The model for a Lawful sorcerer would be one that only focuses on the rituals of banishment.)

All sorcerers can read the ancient language of the Snake-Men.

Sorcerers can eat other sorcerers brains in an attempt to learn any rituals their victim may know.

Characters can carry up to the greater of their strength score or ten number of items. An item is anything one could imagine taking up a non-trivial amount of space. So a ration would take up one item slot, another ration would take up another; armour is a slot; your weapons are each a slot; 100 GP in coins is a slot.

A character takes a -1 to all rolls for each extra item they carry over their allowed amount.

Ascending AC will be used for combat. Players roll a d20 to hit, add their attack bonus, and try and score higher than their opponent’s AC. An unarmoured combatant has an ascending AC of 10.

The attack bonus progression for Fighters is:

| Level | Bonus |

|---|---|

| 1-3 | +1 |

| 4-6 | +2 |

| 7-9 | +5 |

| 10-13 | +7 |

The attack bonus progression for Sorcerers is:

| Level | Bonus |

|---|---|

| 1-3 | +0 |

| 4-6 | +2 |

| 7-9 | +5 |

| 10-13 | +7 |

The attack progression for specialists and psionicsts is:

| Level | Attack Bonus |

|---|---|

| 1–4 | +0 |

| 5–8 | +2 |

| 9–12 | +5 |

| 13–16 | +7 |

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged:

Instead of making opposed rolls during combat, players simply make a normal combat check. If they succeed they roll damage. An enemy can make an armour save to reduce the damage rolled by half. This is inline with what the online Mothership community is doing, and what Sean himself suggested.

Gradient Descent suggests rolling for random encounters every 10 minutes of in game time, or once per human scale room, three times per industrial scale room. As written, there is a 1 in 10 chance for an encounter (rolling doubles on d100). So, relatively infrequently. In my first session there were no random encounters, for example.

An idea I stole from Brendan is to have the dead results on the encounter check also do something. (The infamous Hazard Die) This can add a bit more dynamism into what’s happening during a game. Since this is Mothership I’ll use a D10.

1: Encounter

2-3: Exhaustion

4-5: Expiration

6-9: Environment

10: Easement

Encounter: roll on a random encounter table.

Exhaustion: the characters are hungry or fatigued. They must rest and eat, or take a point of stress.

Expiration: batteries die, oxygen runs dangerously low, etc.

Environment: something about the players immediate surroundings change. Perhaps there are hints of a future encounter.

Easement: a moment of calm, so the players may lose one stress.

I have liked having ‘quiet’ results, so “environment” is the most likely event. I’ll experiment with this over the coming sessions.

by Ramanan Sivaranjan on January 01, 0001

Tagged: